Feeding Alfalfa in Pssm in Horses

1. What is polysaccharide storage myopathy (PSSM)?

The American Quarter Horse Association (AQHA) has funded research into this disease since 1995 and has provided us with the opportunity to learn much about the diagnosis, cause and treatment for this disease. Prior to the development of a genetic test, PSSM was diagnosed by muscle biopsy. The muscle biopsy technique identified an apparent glycogen storage disease and the terms PSSM or EPSM and EPSSM were used to describe the condition. The variety of acronyms used are in part related to preferences of different laboratories, as well as to differences in the criteria used to diagnose polysaccharide storage myopathy. With progress into identifying the genetic basis for PSSM, we now recognize that there is more than one form of PSSM. Our laboratory now distinguishes type 1 PSSM (PSSM1) and type 2 PSSM (PSSM2). Type 1 PSSM is the form of PSSM caused by the genetic mutation in the glycogen synthase 1 () gene. Type 2 PSSM represents one or more other forms of a muscle disease that are characterized by abnormal staining for muscle glycogen in microscopic examination of muscle biopsies.

2. What is type 1 polysaccharide storage myopathy (PSSM1)?

The original research performed by Dr. Valberg on PSSM centered around Quarter Horses with clinical signs of tying-up and abnormal amylase-resistant polysaccharide in their muscle biopsies. This research determined that the horses had 1.8 fold more glycogen (storage form of sugar) in their muscles, a deficit in energy when they exercised and persistent elevations in serum CK activity with exercise unless fed low starch high fat diet. Continued research into PSSM in Quarter Horses resulted in the discovery of a genetic mutation in the glycogen synthase 1 gene in this herd of research horses. Testing of all of the muscle samples submitted to the NMDL that were diagnosed by muscle biopsy as having PSSM showed that not all horses diagnosed with PSSM by muscle biopsy have the mutation. The form of PSSM resulting from the mutation was termed type 1 PSSM.

3. What are the signs of PSSM1 in horses?

In some breeds, horses with the genetic mutation for PSSM1 are asymptomatic. This may relate to differences in diet, exercise and impact of different genotypes in different breeds. Horses with PSSM1 can have signs typically associated with tying-up. These signs are most commonly muscle stiffness, sweating, and reluctance to move in conjunction with increased serum creatine kinase (CK) activity. The signs are most often seen in horses when they are put into initial training or after a lay-up period when they receive little active turn-out. Episodes usually begin after very light exercise such as 10-20 minutes of walking and trotting. Horses with PSSM1 can exhibit symptoms without exercise. During an episode, horses seem lazy, have a shifting lameness, tense up their abdomen, and develop tremors in their flank area. When horses stop moving they may stretch out as if to urinate. They are painful, stiff, sweat profusely, and have firm hard muscles, particularly over their hindquarters. Some horses will try pawing and rolling immediately after exercise. Most horses with PSSM1 have a history of numerous episodes of muscle stiffness at the commencement of training; however, mildly affected horses may have only one or two episodes/year. Rarely, episodes of muscle pain and stiffness can be quite severe, resulting in a horse being unable to stand and being uncomfortable even when lying down. The urine in such horses is often coffee colored, due to muscle proteins being released into the bloodstream and passed into the urine. This is a serious situation, as it can damage the horse's kidneys if they become dehydrated. Very young foals with PSSM1 occasionally show signs of severe muscle pain and weakness. This occurs more often if they have a concurrent infection such as pneumonia or diarrhea.

4. What should I do if a horse is stiff and reluctant to move?

5. How do I know if my horse is having an episode of tying up?

You can read more about Exertional rhabdomyolysis here.

6. Does PSSM1 differ from HYPP?

Hyperkalemic periodic paralysis HYPP is a completely separate muscle disorder in Quarter Horses from PSSM1. The two diseases have different clinical signs, different causes and different treatments.

7. What causes PSSM1 in horses?

An old theory about tying-up is that it is due to too much lactic acid in the muscle. Many exercise studies have proven that this is absolutely not the case with PSSM1. Polysaccharide storage myopathy (PSSM1) is characterized by the abnormal accumulation of the normal form of sugar stored in muscle (glycogen) as well as an abnormal form of sugar (amylase-resistant polysaccharide) in muscle tissue. By definition horses with PSSM1 have a distinctive genetic mutation in the gene. Thousands of horses have been identified with tying-up associated with polysaccharide accumulation in muscles. The mutation causing PSSM1 is a point mutation in the gene that codes for the skeletal muscle form of the glycogen synthase enzyme. The mutation causes this glycogen synthase enzyme to be overactive, increased in activity especially in the presence of insulin resulting in constant production of glycogen. When glycogen is being produced the reciprocal breakdown of glycogen is impaired potentially resulting in a deficit of energy in the muscle cell. Carbohydrates that are high in starch, such as sweet feed, corn, wheat, oats, barley, and molasses, appear to exacerbate PSSM1. That is why they should be avoided and extra calories can be provided in the form of fat. An important part of the management of PSSM1 horses is daily exercise. This enhances glucose utilization, and improves energy metabolism in skeletal muscle. If only the diet is changed, we found that approximately 50% of horses improve. If both diet and exercise are altered, then 90% of horses have had no or few episodes of tying-up.

8. Is PSSM1 inherited?

Yes. Type 1 PSSM is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. Only one parent needs to pass the genetic mutation to its offspring for signs of tying-up to occur. No matter who is selected as the breeding partner there is a 50% chance or greater that a PSSM1 horse's offspring will develop the disease.

9. What breeds are affected by PSSM1?

PSSM1 is a glycogen storage disease that has been found in over 20 different breeds. It was first recognized in horses with Quarter Horse bloodlines such as Quarter Horses, American Paint Horses and Appaloosas and in draft and warmblood breeds with continental European bloodlines (Belgian and Percheron, for example). The degree to which horses exhibit clinical disease with the PSSM1 mutation varies between breeds. This is because diet, exercise regimes and the many interactions between genes can vary from breed to breed. The following table describes the number of randomly samples horses that tested positive for the PSSM11 mutation out of the total number of horses tested as well as the % of horses that were positive for the mutation (prevalence).

Number with PSSM1 Prevalence

-

Number

with PSSM1

Prevalence

-

QH

22/335

6.6%

-

Paint

15/195

7.7%

-

Appaloosa

9/152

5.9%

-

Morgan

2/214

0.9%

-

Percheron

93/149

62%

-

Belgian

58/149

39%

-

Shire

1/195

0.5%

-

Clydesdale

0/48

0%

-

Trekpaard

17/23

74%

-

Comtois

70/88

80%

-

Breton

32/51

63%

Reference: Baird et al Vet Rec. 2010 Nov 13;167(20):781-4. McCue et al J Vet Intern Med. 2008 Sep-Oct;22(5):1228-33

The prevalence of PSSM1 in various Quarter Horse performance types

-

Quarter Horse type

Percent positive for PSSM1

-

AQHA

11.3%

-

Paint

4.5%

-

Halter

28.2%

-

Western Pleasure

8.6%

-

Cutting

6.7%

-

Reining

4.3%

-

Western cow

5.7%

-

Barrel racing

1.4%

-

Racing

2.0%

Reference: Tryon et al J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009 Jan 1;234(1):120-5.

10. How is a diagnosis of PSSM1 established?

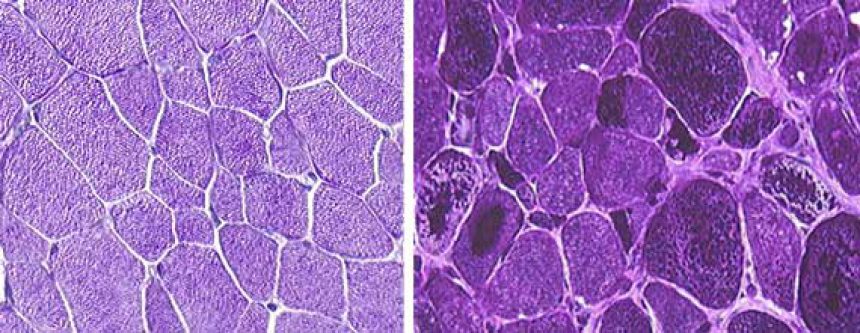

Genetic Testing: Whole blood or hair roots can be submitted for PSSM1 genetic testing to the University of Minnesota Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (800) 605-8787. Genetic testing is also part of the AQHA 5 panel genetic test and is performed at the Veterinary genetics Laboratory at the University of California Davis. Genetic testing is not performed at Michigan State University. We strongly recommend your veterinarian be involved in genetic testing. We cannot make anything more than general recommendations about the disease as we have not evaluated your horse to know if there are any concurrent problems that would make our diet or exercise recommendations contraindicated. Muscle Biopsy: PSSM can be diagnosed based on microscopic evaluation of a muscle biopsy in horses over two years-of-age, however, a definitive diagnosis of the type 1 form of PSSM requires genetic testing. The sample is taken from the semimembranosus muscle, which is part of the rear limb hamstring muscles. Sections of muscle are evaluated with a number of special stains. The periodic acid Schiff's (PAS) stain is used to look at the amount of sugar stored as glycogen in the muscle. With PSSM1, the intensity of this stain is very dark indicating a large amount of glycogen is present in the horse's muscle. Horses with PSSM1 have deep purple inclusions of an abnormal complex sugar stored in fibers. This is the classic diagnostic feature of PSSM1 muscle. The abnormal polysaccharide always remains within the muscle tissues and does not decrease in amount over time.

A normal biopsy (left) and a biopsy from a horse with PSSM1 (right) stained with PAS. Note the lack of a uniform texture in the PSSM1 biopsy. The darker areas in the PSSM1 biopsy indicate the accumulation of excess glycogen and abnormal polysaccharide.

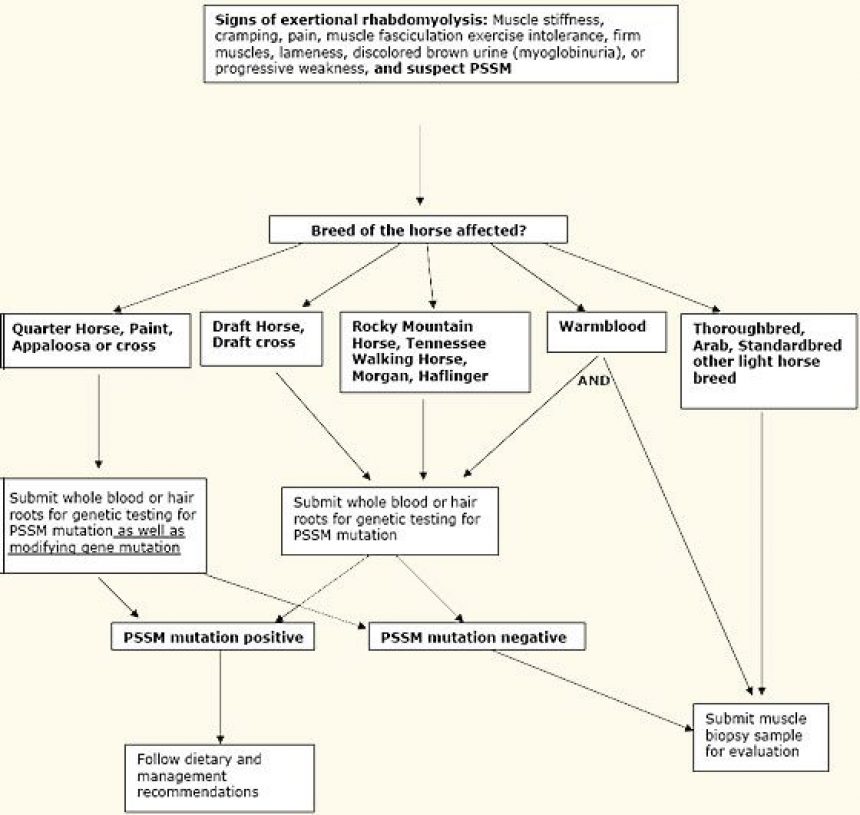

11. How do I know if I should do the genetic test or the muscle biopsy?

PSSM1 is rare to nonexistent in some breeds and therefore testing is not recommended for horses with tying up in breeds such as Arabians, Thoroughbreds and Standardbreds. PSSM1 occurs in Warmbloods but it accounts for less than 10% of the cases of PSSM in this breed (more likely to have type 2 PSSM). The flow chart below can help to decide whether a genetic test is the best approach to investigate tying up in your horse.

12. How do I interpret genetic test results?

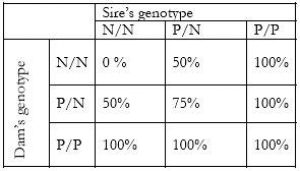

Inheritance of PSSM1: Each horse has two copies of every gene (genotype), one inherited from the dam and one from the sire. Every horse inherits either a normal or a mutant gene form each parent. We have designated the letter P to indicate the mutant PSSM1 gene and MH to indicate the mutant MH gene. A normal horse is designated as N/N. A horse with PSSM1 may be heterozygous P/N or rarely homozygous P/P for the mutation. Those horses that are P/P are often more severely affected and harder to manage. The PSSM1 mutation is inherited in a dominant fashion, meaning that one copy of the mutation can cause PSSM1. This is different from diseases such as HERDA and GBED, which are inherited in a recessive fashion, where 2 copies of the mutant gene are required for disease. Because PSSM1 is inherited in a dominant fashion the chances of an affected foal being born are dependent on the genotype of the parents as follows:

Thus any time a horse with PSSM1 is bred there is a minimum chance of 50% of an affected foal being born even if the selected mate is completely normal. The risk of producing an affected offspring when breeding a horse with PSSM1 is much higher because it is a dominant disease. Unlike the recessive diseases, where a horse with one copy of the gene is a "carrier" a horse with one copy of the PSSM1 mutation has PSSM1. There appears to be a second genetic mutation (MH) that makes signs of PSSM1 more severe in Quarter Horses and related breeds. The PSSM1 and MH genetic tests are recommended in Quarter Horse-related breeds with very recurrent or difficult to mange episodes of tying up, elevated body temperature with tying up or severe anesthetic reactions. Both tests are done at the University of Minnesota. Not all cases of tying up are caused by the PSSM1 mutation. If a horse is N/N but is showing signs of tying-up or muscle pain, it is possible that the horse has another muscle disorder which must be diagnosed by muscle biopsy.

13. How do I prevent another episode of tying-up in my PSSM 1 horse?

Rest: For chronic cases, prolonged rest after an episode appears to be counterproductive and predisposes PSSM1 horses to further episodes of muscle pain. With PSSM1 it is NOT advisable to only resume exercise when serum CK activity is normal. Rather, horses should begin small paddock turn out as soon as reluctance to move has abated. Providing daily turn out with compatible companions can be very beneficial as it enhances energy metabolism in PSSM1 horses. Grazing muzzles may be of benefit to PSSM1 horses turned out on pastures for periods when grass is particularly lush. Most PSSM1 horses are calm and not easily stressed, however, if stress is a precipitating fact, stressful environmental elements should be minimized. Reintroducing exercise: Re-introduction of exercise after an acute episode of ER in PSSM1 horses needs to be gradual. Important principles include 1) providing adequate time for adaptation to a new diet before commencing exercise (2 weeks), 2) recognizing that the duration of exercise is more important to restrict than the intensity of exercise (no more than 5 min walk/trot to start) 3) ensuring that exercise is gradually introduced and consistently performed and 4) minimizing any days without some form of exercise. Exercise should begin with light slow uncollected work on a longe-line or under saddle beginning with once a day for 3-5 minutes at a walk and trot. This initial work should be very mild and very short in duration. Work at a walk and trot can be gradually increased by two minutes each day. When the horse can exercise for 15 minutes, a five-minute break at a walk can be provided, and then a few intervals of walk and trot can gradually be increased. At least three weeks of walk and trot should precede work at a canter. Exercise: Regular daily exercise is extremely important for managing horses with PSSM1. Even 10 min of exercise has been shown to be extremely beneficial in reducing muscle damage with exercise. Once conditioned, some PSSM1 horses thrive with 4 days of exercise as long as they receive daily turn out. For riding horses with type 2 PSSM1, a prolonged warm-up with adequate stretching is recommended. Rest periods that allow horses to relax and stretch their muscles between 2 – 5 min periods of collection under saddle may be of benefit. Adherence to a strict diet will also help horses with PSSM1. When designing a diet for horses with PSSM1 there are several important considerations. We advise consulting a nutritionist. Turn out is very beneficial for PSSM1 horses as they get regular exercise during turn out, however consider the sugar content of the pasture when designing a diet. If the pasture is lush, grazing should be restricted either by moving to another pasture, dry lot or by using a grazing muzzle. 1) Caloric balance: Many horses with PSSM1 are easy keepers and may be overweight at the time of diagnosis. If necessary, caloric intake should be reduced by using a grazing muzzle during turn-out, feeding hay with a low nonstructural carbohydrate content (NSC) at 1 to 1.5% of body weight, providing a low calorie ration balancer and gradually introducing daily exercise. Rather than provide dietary fat to an overweight horse, fasting for 6 h prior to exercise can be used to elevate plasma free fatty acids prior to exercise and alleviate any restrictions in energy metabolism in muscle. 2) Selection of forage: Quarter Horses have been shown to develop a significant increase in serum insulin concentrations in response to consuming hay with an NSC of 17% , whereas insulin concentrations are fairly stable when fed hay with 12% or 4 %NSC content (Borgia et al 2011). Because insulin stimulates the already overactive enzyme glycogen synthase in the muscle of type 1 PSSM1 horses, selecting a hay with 12% or less NSC is advisable. The degree to which the NSC content of hay should be restricted below 12% NSC depends upon the caloric requirements of the horse. Feeding a low NSC hay of 4% provides room to add an adequate amount of fat to the diet of easy keepers without exceeding the daily caloric requirement and inducing excessive weight gain. For example, a 500-kg horse on a routine of light exercise generally requires 18 MCal/day of digestible energy (DE). Fed at 2% of body weight, a 12% NSC mixed grass hay almost meets their daily caloric requirement by providing 17.4 MCal/day. This with a12%NSC hay there is only room for 0.6 MCal of fat per day (72 ml of vegetable oil) in order to achieve 18 MCal of energy. In contrast, a 4% NSC Blue Grama hay would provide 13.5 MCal/day which would allow a reasonable addition of 4.5 MCal of fat per day (538 ml of vegetable oil). 3) Selection of fat source: My initial approach would be to get the horse moving comfortably with a low starch/sugar diet and to get the horse into a suitable weight range before adding fat. The type and amount of fat to add depends on the individual horse and on the horse's weight and owner's budget. In an easy keeping horse, when you add fat the cheapest way to do so is to add oil or a solid fat supplement onto a pelleted ration balancer that provides enough energy. Check the caloric density of the ration balancer, you may want to use one for overweight horses. Suitable oils include soybean, corn, safflower, canola, flaxseed, linseed, fish, peanut and coconut. The amount of oil can be added gradually monitoring the horses exercise tolerance and weight. The amount added is usually between 1/2 and 2 cups. Horses with too little fat often have a cranky attitude toward exercise. Low starch high fat concentrates: These feeds are only suitable if horses are going to consume enough to get a balance of vitamins and minerals as well as some fat. Rice bran and its products are palatable to most horses, have a moderate NSC content ~25% by weight, contain ~20% fat by weight as well as vitamin E and are naturally high in phosphorus. The NSC component of rice bran can vary if the manufacturing process is not careful to exclude the white rice grain. If you feed a product like ReLeve or Ultium you usually need at least 4 lbs to achieve a balanced diet and this may be too many calories in lightly worked overweight horses. The beneficial effect of the low starch, high fat diet is believed to be the result of less glucose uptake into muscle cells and provision of more plasma free fatty acids for use in muscle fibers during aerobic exercise.(Borgia et al, 2010) Quarter Horses naturally have very little lipid stored within muscle fibers and provision of free fatty acids may overcome the disruption in energy metabolism that appears to occur in PSSM1 Quarter Horses during aerobic exercise. This beneficial effect requires that horses are trained daily to enhance enzymes involved in fat and glucose metabolism. Many feed companies have low starch fat formulated diets for horses that work for horses with PSSM. The dietary recommendations based on total daily calorie intake are provided in the table belwo to help nutritionists select the most appropriate feed/ Dr Valberg worked with KER and Hallway Feeds (1-859 255-7602) to develop the first of these diets called Re-Leve™** . The Releve Concentrate works well for PSSM1 in moderate to heavy work that require at least 4 lbs of concentrate a day. If fed in lesser amounts it does not provide adequate fat for PSSM horses. This is also a good diet for young growing horses with PSSM1. Weanlings can be fed 6.5 lbs of Re-Leve™ and mixed grass/alfalfa hay (8 lbs/day). Yearlings can be fed 8 lbs Re-Leve™ and a 50-50 alfalfa: grass hay (9 lbs/day). ** Do not feed additional selenium with this feed, as it is fully supplemented. **Conflict of interest statement: A portion of the profits from Re-Leve™ is contributed to Stephanie Valberg. Vegetable oils and rice bran with medium and long chain fats can also be added to roughage base or a ration balancer as a fat source. Gradually adding up to 2 cups per day. Add 600 U of vit E per cup of oil to the diet. While a good balance of Omega 3 to 6 ratio may be important for other health reasons it does not appear to impact the response to fat diets in PSSM1 horses. In addition to a salt block in the stall, an electrolyte supplement should be offered to horses in hot, humid weather. Table 1. Feeding recommendations for an average-sized horse (500 kg) with PSSM1. The amounts are expressed as the percentage of total digestible energy (DE or megacalories) that should be fed with regard to nonstructural carbohydrates (NSC), fat, protein and forage. A nutritionist can select the appropriate feed and amounts based on this information. Digestible Energy 16.4 20.5 24.6 32.8 % DE as NSC PSSM1 <10% <10% <10% <10% % DE as fat PSSM1 20% 20% 15%-20% 15%-20% Forage % bwt 1.5- 2.0 % 1.5- 2.0 % 1.5- 2.0 % 1.5- 2.0 % Protein (grams/day) 697 767 836 906 Calcium (g) 30 33 36 39 Phosphorus (g) 20 22 24 26 Sodium (g) 22.5 33.5 33.8 41.3 Chloride (g) 33.8 50.3 50.6 62 Potassium (g) 52.5 78.3 78.8 96.4 Selenium (mg) 1.88 2.2 2.81 3.13 Vitamin E (IU) 375 700 900 1000

Maintenance Light

Exercise Moderate

Exercise Intense

Exercise

(Mcal/day)

horses

horses

Daily requirements derived from multiple research studies (% NSC and % fat) and Kentucky Equine Research recommendations. From: 2003. McKenzie EM, Valberg SJ and Pagan J. In: Current Therapy in Equine Medicine 5. ed Robinson E Saunders, Philadelphia PA, 2003, pp 727-734.

14. Can my horse be cured?

When the described diet and exercise routines were followed we found that all horses improved, and >75% of horses stopped tying-up. PSSM1 horses, however, will always be susceptible to this condition and if their exercise schedule is disrupted. If they become ill from other causes, they may again develop clinical signs again. If this occurs, they should go back to the fitness program described above using longeing or round pen work. Many horses with this condition are happy trail horses, successful pleasure horses, and useful ranch horses. The greatest difficulty in owning a horse with PSSM1 is the time commitment to keep the horse fit and the moderate expense of special feeds.

15. Where can I find out more about PSSM1?

Dr. Valberg and other members of the lab team have published their research on PSSM1 in many general interest and scientific articles. Scientific articles by Dr Valberg and colleagues

Hunt LM, Valberg SJ, Steffenhagen K and McCue ME. An Epidemiologic Study of Myopathies in Warmblood Horses. Equine Vet J. 2008 Mar;40(2):171-7.

16. Watch a 2017 seminar on PSSM

View the seminar here

Source: https://cvm.msu.edu/research/faculty-research/comparative-medical-genetics/valberg-laboratory/type-1-polysaccharide-storage-myopathy

0 Response to "Feeding Alfalfa in Pssm in Horses"

Postar um comentário